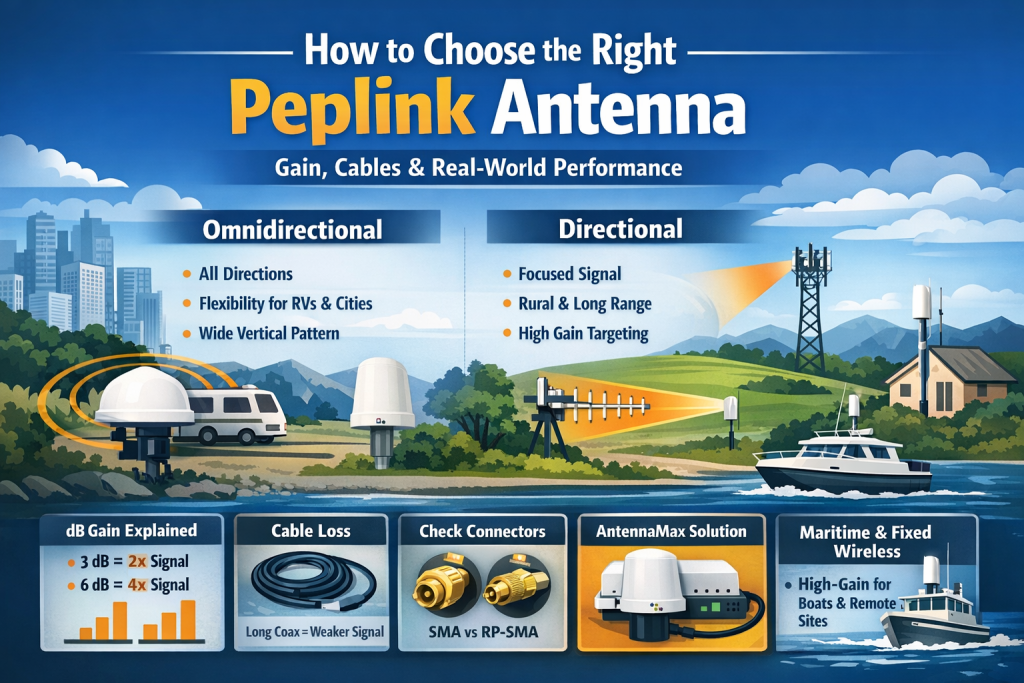

Choosing the Right Peplink Antenna: What Actually Matters (and Why It Can Outperform a Modem Upgrade) When people troubleshoot slow or unreliable cellular connectivity, they often jump straight to the modem or carrier. In Peplink’s webinar on antenna selection, the big takeaway was simple: antenna choice is just as critical as modem choice, and the right […]

Ericsson U.S. Data Breach: What Cradlepoint Users Should Know

Ericsson Inc., the U.S. arm of Swedish telecom giant Ericsson, has disclosed a significant data breach stemming from a hack of one of its third-party service providers. The incident has raised questions across the networking industry, including among customers of Cradlepoint — a company Ericsson acquired in 2020 and operates under its Ericsson Enterprise Wireless […]

Starlink Kills In-Motion Use on $5 Standby Plan

If you have been relying on Starlink Standby Mode as a low-cost backup for road trips and remote travel, this week brought an unwelcome surprise. SpaceX has officially blocked in-motion use for subscribers on the $5 per month Standby Mode plan, ending what many considered the best bargain in satellite internet for mobile connectivity. What […]

T-Mobile T-Satellite Is Getting a Huge Upgrade

T-Mobile’s T-Satellite service is about to get significantly more capable. Thanks to SpaceX’s next-generation Starlink V2 satellites, the direct-to-cell service that launched commercially in July 2025 is heading toward a future where your phone can stream, browse, and make calls from anywhere — even where no cell tower has ever reached. What T-Satellite Is Today […]

FCC Moves to Bring Telecom Call Centers Back to the US

If you have ever called your wireless carrier and spent twenty frustrating minutes trying to communicate with a support agent halfway around the world, the FCC just heard you. FCC Chairman Brendan Carr announced on March 4, 2026, that the commission will vote this month on a sweeping proposal to push telecom companies to bring […]

Starlink Cuts Prices: $39/mo Deal Through March 31

If you have been sitting on the fence about Starlink, here is your nudge. Through March 31, 2026, SpaceX is running one of its most aggressive residential pricing promotions yet, dropping entry-level service to just $39 per month for the first six months. Three plan tiers are on the table, and one of them even […]

Find the Best Signal Before You Buy: Introducing 5Gstore Tower Finder App

One of the most common questions we get at 5Gstore is simple: “Will a cellular router work at my location?” It sounds like a straightforward question, but the answer depends on a surprising number of variables: which carrier you are on, how far you are from the nearest tower, what frequency bands are being used, […]

FIPS 140-3 and Semtech AirLink Routers

If you deploy Semtech AirLink routers in government, public safety, or any environment that requires federal cryptographic compliance, there is an important deadline on the horizon. On September 21, 2026, NIST will officially move all FIPS 140-2 validations to historical status as part of its broader cryptographic modernization effort. This marks the formal transition to […]

The Complete Guide to 5G Routers: Speed, Reliability, and the Future of Connectivity

The way businesses connect to the internet has changed permanently. Fixed broadband works great until it doesn’t, and for remote sites, mobile deployments, or mission-critical operations where downtime is not an option, a 5G router is no longer a luxury. It’s infrastructure. Whether you’re running a construction trailer in a field, keeping a fleet of […]

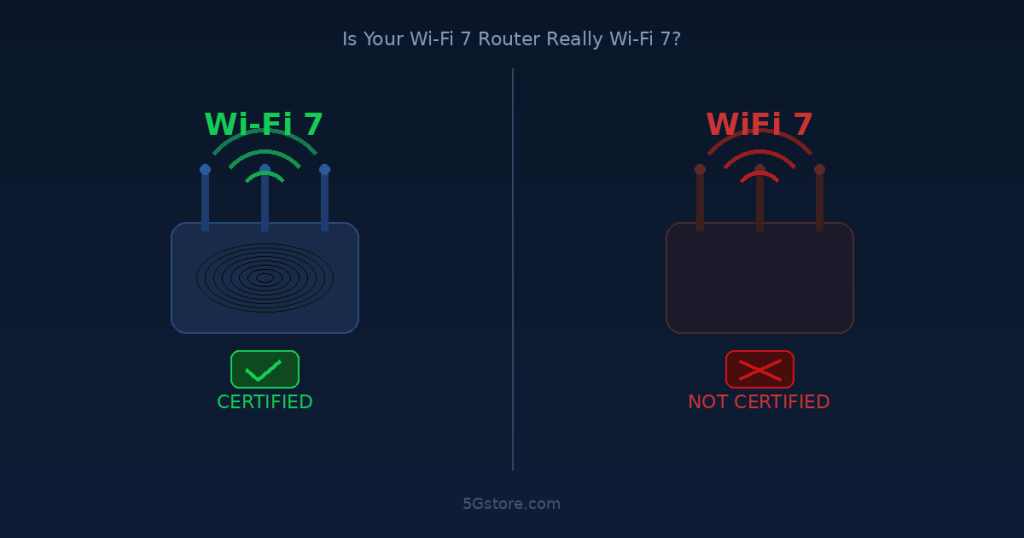

Is Your Wi-Fi 7 Router Actually Wi-Fi 7?

Is your WiFi 7 Router listed as WiFi 7 or Wi-Fi, missing the hypen or not? It matters Wi-Fi 7 has been marketed as the biggest leap in wireless technology in years. Faster speeds, lower latency, smarter band management — the promises are impressive. But there is a growing problem hiding in plain sight: a […]